Learning to Teach – meet the 19-year-old technology teacher from Partskhanakhanevi

“Teachers still think I am a student,” says 19-year-old Akaki Pertsuliani – “and pupils call me ‘Teacher Akaki’ and sometimes just my first name.” But Akaki Pertsuliani really is a teacher at the Partskhanakhanevi Public School No. 2 of Tskaltubo Municipality as well as a Tech Club trainer, programmer, technology guide and, simply, everybody’s diligent supporter at school.

A few years ago, it would have been difficult to imagine an 18-year-old student becoming a teacher at his own school, but the information age often turns our assumptions on their heads, and so here we are – at the school that cares for the technological future of children and the country.

Everything began a few years ago when Varden Nikabadze, director of the school, decided to test the use of ‘Google Classroom’ in the school’s academic and administrative work. This was followed by the creation of a school website-based digital library, and then the 3D Club where Akaki made his first steps in technology.

Akaki, already well-known for dismantling and reassembling toys, reading encyclopedias and displaying exceptional interest in information technologies, quickly got the feel of the new 3D printer, and was soon printing his own 3D creation – a scale model of the school.

Then, as semi-finalists of the national school leadership competition, the school and its director received 10 DJI Tello EDU training drones from Ilia State University. For Akaki, who was already interested in programming, this was another driver deepening his interest in information technologies. Shortly after, using the ‘Python’ programming language, Akaki and the school director developed a programme for operating the drone. As an XI-XII grade student, he was an assistant to the director and was actively involved in teaching children how to operate the drones.

“We studied the drones that had been given to the director so well that we wrote the application to operate them. This application makes it possible to control the drone: to fly it, set direction, take photos or videos, and perform various maneuvers,” says Akaki Pertsuliani.

Host and Trainer

Akaki was a XII-grade student and had already invented several games when as part of the EU-funded Skills4Jobs programme, Ilia State University launched the Youth Tech Clubs Network. The project invited schools from eight regions of Georgia to train their students in coding or technical entrepreneurship. Partskhanakhanevi Public School No.2 decided to teach its students “Python” under this project.

“Python is an important programming language used in many fields – to programme a robot, or for web development. At the first stage I was the host, which meant I had to ensure student attendance and motivate them to cover the course and care for the technical serviceability of the laboratory. But they soon offered me to be a trainer. When I was the host, it was evident that I wanted more, as I knew more and was developing. Then I was trained in programming, and my knowledge was assessed. Now I teach the children Python and web development,” says Akaki Pertsuliani.

Akaki is not only trainer of the tech club. Through the club work, he gives the IX-XII grade students vital knowledge for the contemporary world, but he also pays attention to the lower grade students.

A teacher at 19

Akaki explains the basics of programming and electricity to the students and teaches block programming to the lower classes. In VI, VII, and VIII grades he explains robotics and electricity, and introduces programming as well – i.e. programming the robots. In the higher grades Akaki starts teaching web development and “Python”.

Like other clubs at the school, the tech club is voluntary. Initially, few students signed up, but now their number has increased dramatically – “At least 50% of the IV to XII grade students at our school attend my tech lessons,” Akaki says.

The atmosphere in his lessons is relaxed and benevolent. We are attending one of his lessons in the gym where IV-graders operate the drones using block programming. In response to their restlessness Akaki smiles and says that sometimes he himself feels like a child (especially at this school where he was so recently a student), adding it is not easy for him to get angry with the pupils. He has a friendly relationship with the children, adding he doesn’t want to interfere with their play – indeed he often encourages them to have more fun.

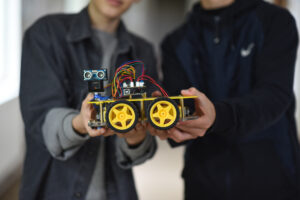

Akaki’s approaches and teaching methods have tangible results. His graduates from the tech club write games using “Python”, and two of his students have assembled a small robot from spare parts. They did everything with the help of “Arduino” (an electronic prototyping platform), which their young teacher uses to explain electricity to his students.

In the laboratory, VI and VII grade students Aleko and Nugo showed us their robot prototype and told us how they wrote their first computer game using “Python.”

“The case of Aleko and Nugo is a huge success for me as they mastered technologies very well,” Akaki explains. “Another achievement is that we introduced technical thinking into the higher grades and familiarised the children with this field. Maybe not all of them will choose a career in technologies, but they will have at least the basic knowledge. They might not all master programming, but they will at least understand what happens in a device, and how.”

Programmer

Not everybody can master technologies, especially in the upper grades. Akaki considers that the reason for this is the lack of background knowledge, and he counts more on his younger students. Nevertheless, many students are attracted by Akaki’s intellectual curiosity and his relentless desire to test himself.

“Programming and mistakes are aligned; they are almost one and the same,” says Akaki. “Any time you start something new, there are chances that you will make at least one mistake. The best of all is the moment when you solve these – your own problems, fix them and see a huge result, e. g. when the game is on and working. Then your interest deepens further, and you strive to see what else you can do.”

In Georgia, like in many other countries of the world, there is a huge demand for programmers, as rapid technological progress meets the scarcity of skilled human resources.

Akaki believes that the development of the country is impossible without increasing the number of professionals in this field: “If children know technologies and programming from school, they will be able to find jobs soon and get experience as well. It is a rather high-earning field, and it is also important for the nation’s economy.”

Teacher by vocation

“If I look at my childhood interests, I always liked teaching and explaining, especially when it was related to technologies,” says Akaki, adding that for him, “gaining more knowledge is a means to share more knowledge with others”.

For Akaki, technology is there to support, rather than disrupt, humans and nature. It makes human endeavour easier and leaves space for more creativity The more developed the technology becomes, the more optimised it is to the world, he says, citing the example of electric cars – in the future these will help minimise the damage to the environment caused by transport.

Combating Disinformation

The young teacher’s work is not limited to caring for the generation of tomorrow. He often talks with members of the older generation and tries to counter their fears of technology. This happens almost every time when he is asked to repair other (older) teachers’ or simply older villagers’ tech devices.

Akaki says people are scared by technologies and have misconceptions about new devices or aspects of the digital world. These may be the myths related to harmfulness of 5G networks, or general vulnerability to various types of disinformation.

“I try to explain to the people around me that the technology in this world is neither so complicated, nor so harmful,” he says.

And Akaki is never tired of repairing devices and explaining complicated topics in simple words:

“If somebody’s computer is out of order or damaged, I am used to repairing it effortlessly. They see that I do these ‘difficult’ things easily and I think they develop an interest. Simultaneously, I must often explain to the people around me that not everything they see on their smartphones or on social networks is always true. The older generation thinks they should trust everything they see on the Internet. When this generation was younger, none of this existed, there were no computer graphics and nobody could manipulate images and text so easily.”

Programmer and Teacher of the Future

What type of future lies ahead for someone like Akaki, who likes to learn and teach equally?

“My dreams came true after my graduation from school. I became a teacher, and I know technologies. The next step is to develop further and be a strong programmer,” says Akaki.

As a programmer, Akaki wants that to take part in solving big and important problems, while as a teacher he would like to be able to share more knowledge with children.

“My aspiration is to be a programmer. I want to learn this profession more thoroughly. Despite the level of my knowledge in the field, I am never satisfied, and I am always interested in what happens deeper inside,” he says, adding that he would like to create programs that are equally comprehensible to the young generation and older people.

“As Georgia has few programmers, I want to stay in my country and support Georgians in their development,” Akaki insists.

The 19-year-old technology teacher from Partskhanakhanevi school No.2 is one of those rare people who feels the technological heartbeats of the modern world, and is aware of the need to adapt to new realities. It is not easy to tell exactly what will follow, but one thing he knows for sure – learning and teaching, in one form or another, will always be present in his work.

Today, Mamia Pantsulaia Public School No.2 of the Tskaltubo Municipality village of Partskhanakanevi is a shining example that technological change can take place in Georgian public schools. At this school you will meet the children who often look up at the sky – their eyes searching for the drones which they have programmed themselves.

Public schools in Shida Kartli, Kakheti, Imereti, Adjara and Samegrelo can still enrol into the EU “Youth Tech Clubs Network” project, and open youth tech clubs at their schools. To do so, they must register through this link.

“If at least 30% of the children from this school choose technological professions, this would be a huge achievement for us, and for the entire country,” says Varden Nikabadze, the director of Partskhanakhanevi Public School No.2. At this school, achieving this goal depends on a 19-year-old teacher and trainer, who promises the school, its students, the old and new generations, that he will learn more so he can teach them more.

Author: Khatia Tordua

Article published in Georgian by On.ge

MOST READ

RELATED PROJECTS

SEE ALSO

No, time is not on Russia‘s side

A hands-on approach to boost youth employment in Georgia

Taking health into their own hands: women’s empowerment in the remote villages of Georgia

A woman publisher in a male-dominated industry – the path to a big dream

Be one step ahead of a hacker: check simple cybersecurity tips!

More campaign pages:

Interested in the latest news and opportunities?

This website is managed by the EU-funded Regional Communication Programme for the Eastern Neighbourhood ('EU NEIGHBOURS east’), which complements and supports the communication of the Delegations of the European Union in the Eastern partner countries, and works under the guidance of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, and the European External Action Service. EU NEIGHBOURS east is implemented by a GOPA PACE-led consortium. It is part of the larger Neighbourhood Communication Programme (2020-2024) for the EU's Eastern and Southern Neighbourhood, which also includes 'EU NEIGHBOURS south’ project that runs the EU Neighbours portal.

The information on this site is subject to a Disclaimer and Protection of personal data. © European Union,