Female Leaders: Changing the Agenda

“No country can ever truly flourish if it stifles the potential of its women and deprives itself of the contributions of half its citizens.” – Michelle Obama, 2014.

The path to gender equality is difficult and stony. Starting with the suffragists to modern-day feminists, women and men have fought for women’s right to vote and hold office. Luckily, we can see the actual progress as of 2015 – women worldwide have the right to vote. Today, there are several countries led by females (Germany, New Zealand, Denmark, etc.), and some states have a cabinet dominated by women (Finland and Rwanda). Women represented by a woman are more interested in and more involved into politics; they develop the feeling of being more skilled and effective than those represented by a man. The progress is real, but it is still uneven enough because, with the global female population share of 50 percent, women make up only about 24 percent of parliamentarians in the world. It shows us that there are still many things we must achieve on the path to gender equality in politics.

I am lucky to live in the XXI century when females have so many rights and opportunities: to obtain higher education, get a job, choose whether they want to marry and have kids or not, to vote and to be elected. Nevertheless, there are still some problems that women are facing. They participate in the elections and run for the offices more frequently than before, yet the number of women in politics and government is still far behind men’s numbers. Women in politics, as well as in their daily life, still face structural, socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural barriers.

At the same time, some researches have been produced that proved the positive impact of female politicians on the country’s development. Thus, the study by Supriya Garikipati, of the University of Liverpool, and Uma Kambhampativ, of the University of Reading, says that female-led nations handled the first months of the coronavirus pandemic thoroughly better than male-led ones. The researchers have focused on the two main questions:

- Are there any significant and systematic differences in the COVID-outcomes of male and female led-countries in the first quarter of the pandemic?

- Second, can it be pointed to any differences in male and female leaders’ policy measures that might explain the differences in outcomes?

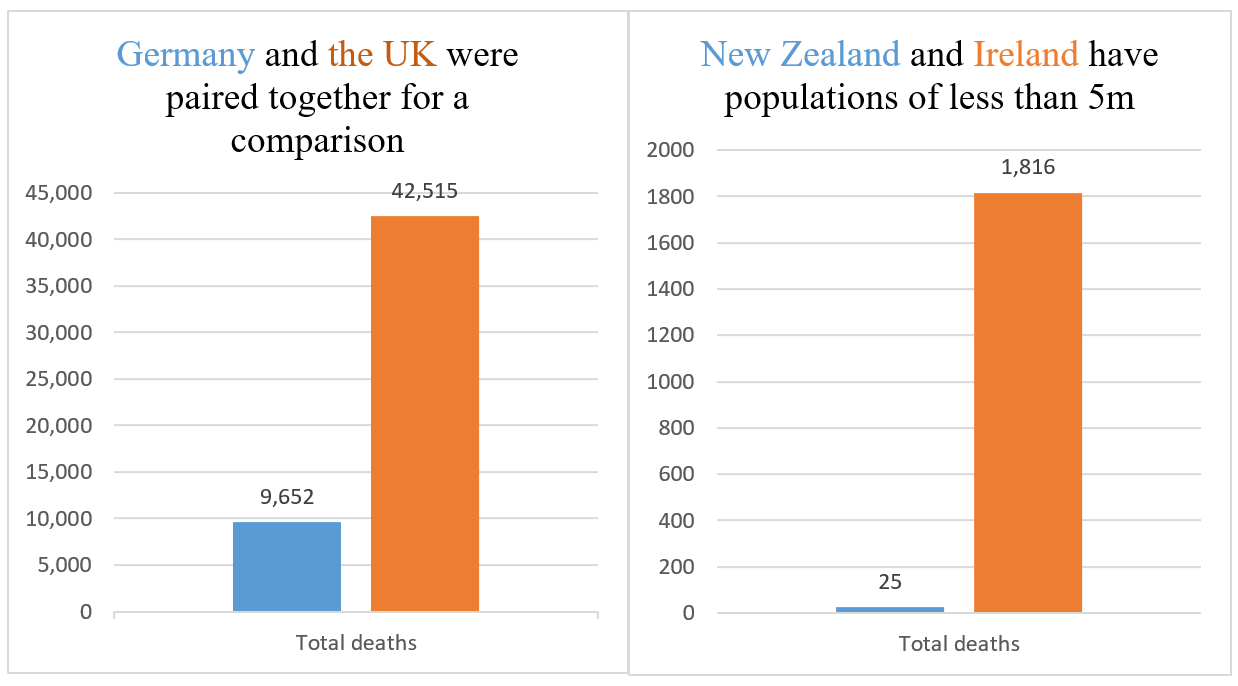

In particular, out of 194 countries in the database, constructed specifically for this purpose, only 19 (<10%) are female-led ones. Researchers analyzed those with similar characteristics based on variables like GDP per capita, population, population density, and population over 65 Years. They also chose a “nearest neighbour” for each country. As an example, they compared the number of death cases in Germany (female-led) and the UK (male-led); Serbia (female) and Israel (male); New Zealand (female) and Ireland (male). As a result, there are some significant and systematic differences as female-led countries have fewer deaths (see in the charts below).

Numbers rely on public data from multiple sources (data correct to 8 October 2020)

The next question discussed was why such differences took place.

Firstly, it is claimed that there is a gender difference in attitude to risk. In terms of the COVID-deaths at lockdown, women leaders wanted to averse risk, so they chose to close their countries much earlier in comparison to their male colleagues. Such an attitude may show that women leaders were “clearly prepared to take more risk” in the economy’s domain than male leaders. There is evidence in psychology, which demonstrates that men and women act very differently in stressful situations. Women are seen to respond more strongly and intensely than men when anticipating negative outcomes (see Fujita et al., 1991; Kring and Gordon, 1998).

Secondly, there is a gender difference in leadership styles. Eagly and Johnson (1990) came to the conclusion that both the presence and absence of differences can be found between the sexes. Laboratory experiments and assessment studies showed evidence to suggest that leadership styles were somewhat gendered as men are likely to lead in a ‘task-oriented’ style and women in an ‘interpersonally-oriented’ manner. It means that women tend to adopt “a more democratic and participative style and a less autocratic or directive style” than men. Indeed, such a style has raised a lot of praise in the ongoing crisis. For example, Norway’s Prime Minister, Solberg, spoke directly to children answering their questions. Ardern, New Zealand’s Prime Minister, talked with her citizens through Facebook’s lives. In Germany, Merkel’s government considered a variety of different information sources in developing its coronavirus policy, including epidemiological models, data from medical providers, and evidence from South Korea’s successful program of testing and isolation, so they have achieved a death rate drastically lower than those of the other Western European countries.

The researchers said they hoped the study would “serve as a starting point to illuminate the discussion on the influence of national leaders in explaining the differences in country COVID-outcomes”. With it help, the proved that gender differences in leadership style and attitude to risk are present. Moreover, we can contemplate how these differences influence our daily lives and economic systems in the ongoing crisis.

I believe it is fair to say that women as politicians are underestimated. Men and women have to work together equally to solve the myriad of problems in their countries. To meet worldwide development goals and build reliable, defensible democracies, women must be encouraged, empowered, and supported in becoming strong political and community leaders.

References

- Garikipati, Supriya and Kambhampati, Uma, Leading the Fight Against the Pandemic: Does Gender ‘Really’ Matter? (June 3, 2020)

- Fujita, Frank, Ed Diener, and Ed Sandvik. 1991. “Gender Differences in Negative Affect and Well-Being: The Case for Emotional Intensity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3): 427–34.

- Kring, Ann M and Albert H. Gordon.1998. “Sex Differences in Emotion: Expression, Experience, and Physiology,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3): 686-703.

- Eagly, Alice H. and Blair T Johnson. “Gender and Leadership Style: A Meta-Analysis” 1990. CHIP Documents. 11. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/chip_docs/11 (accessed 05/10/2020)

- Remarks by the First Lady at the Summit of the Mandela Washington Fellowship for Young African Leaders. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/07/30/remarks-first-lady-summit-mandela-washington-fellowship-young-african-le (accessed 15/10/2020)

More campaign pages:

Interested in the latest news and opportunities?

This website is managed by the EU-funded Regional Communication Programme for the Eastern Neighbourhood ('EU NEIGHBOURS east’), which complements and supports the communication of the Delegations of the European Union in the Eastern partner countries, and works under the guidance of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, and the European External Action Service. EU NEIGHBOURS east is implemented by a GOPA PACE-led consortium. It is part of the larger Neighbourhood Communication Programme (2020-2024) for the EU's Eastern and Southern Neighbourhood, which also includes 'EU NEIGHBOURS south’ project that runs the EU Neighbours portal.

The information on this site is subject to a Disclaimer and Protection of personal data. © European Union,