European identity and policies that could help unify Europeans

Nowadays, the European Union is a principal political actor on the continent which endeavors to connect its member states together in order to frame European community with a relatively explicit European identity. Nevertheless, this process is not straightforward as all countries of the “old continent” have their own sense of identity, which cannot be utterly waned. Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern European states all have something that is unparalleled and that varies them from each other. Thus, it is extremely complex to build a common European identity, but relying on its diverse and coherent policies, the EU anticipates that Europeans soon will assume a common European identity contingent on certain European shared values and laws.

First steps towards European Integration

The contemporary understanding of Europe emanates from the period of Enlightenment. Throughout the centuries, Europe was a symbol of Christian Culture, but after transformation from a traditional, rural, agrarian community to a secular, urban, industrial society, the term Europe gained more significance. It became the symbol of change, innovation, improvement and of expanse that is oriented on dignity, fairness, equality, respect and independence.

After the rise and rule of the great Roman and Byzantine empires, the emergence of the Italian fascism and the Soviet communism dictatorships, and the outbreak of the two destructive world wars, Europeans came to an understanding that they should form Europe which would bring peace, stability and economic prosperity of its people. However, constructing the common European identity was not a feasible or easily accomplishable task. It took reasonable time and great patience.

The initial move towards the European integration exclusively belonged to the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill. After the disastrous World War II and the humanitarian crises in Europe, he applied critical thinking to rebuilding and restoring the continent in a manner in which peace would be maintained. “We must build a kind of United States of Europe. In this way only, will hundreds of millions of toilers be able to regain the simple joys and hopes which make life worth living” – stated Churchill.

Later, the Council of Europe was founded in 1949 based on Churchill’s ideas. However, this organization was not something that contributed to the constructing of the European identity. The European states were terrified of being divested of their sovereignty and did not grant this institution supreme authority. Moreover, Europe during the period of establishment of the Council of Europe was already divided into two separate areas: Eastern and Western Europe. Eastern Europe was taken away by the Soviet Union and was stuck behind the “iron curtain”.

When Europeans realized that it was inconceivable to establish the federal states of Europe, alternative ways of integrating Europe were considered. The main political figures of the continent joined together to form a common European economy as they estimated that the integration in one bailiwick would cause an integration in another area of interest, and gradually, the common European identity would be an inevitable outcome.

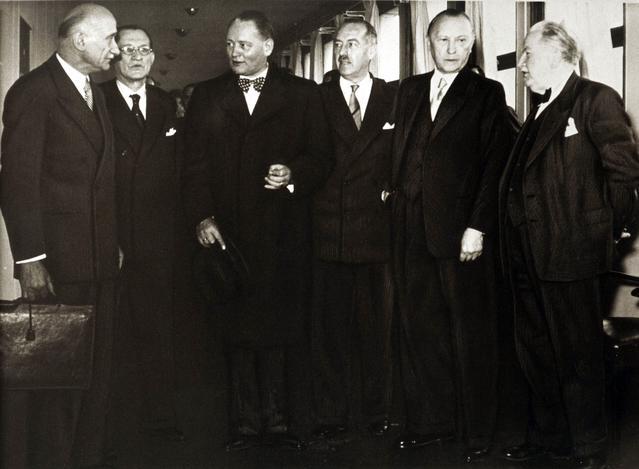

The founding fathers of the EU / Photo Courtesy of the Multimedia Centre at European Parliament.

The first organization integrating Europeans with common economic interests was the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). Jean Monnet, one of the key figures in establishing the ECSC deemed that this was the process of spillover and the consolidation in the economic sphere would bring the integration in another area in the future.

The enlargement process

One of the pioneer members, who were involved in setting up the common European community were France, Italy, West Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. But the immediate success in the organization’s politics enticed progressively more countries and the organization had enlarged several times. First, it occurred in 1973, when UK, Denmark and Ireland became the members of the union, subsequently in 1981 the enlargement was followed by Greece, and in 1985 – by Spain and Portugal.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the EU was joined by Austria, Finland and Sweden in 1995 and during the ultimate Eastern Enlargement in 2004, European family approved Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Cyprus, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia. Western Europeans were hesitant over accepting the Eastern European countries as they were considered as Soviet satellite states, thinking that they were politically and economically unstable and it would cause a great deal of problems within the organization. However, the Eastern European countries were enthusiastic to adopt deliberate policies in order to become more democratic, and as a consequence, sooner or later deserve the chance to join the union.

EU policies that could help construct the common European identity

Needless to say that the steps taken towards integration were irreversible, however, they still were not enough for constructing the common European identity. The process of developing shared European identity was highly challenging, particularly during the period of two world wars and the Cold War. The cooperation among European states mostly implicated integration in the economic sector, although since the 1980s, they undertook to integrate on political and cultural levels.

In 2000 the slogan of the European Union “United in Diversity” began to be used. It indicates the integrity of Europeans not only in the context of maintaining peace and prosperity, but also unity in terms of respecting the diverse cultures, traditions and languages throughout the continent. By developing and implementing various cultural policies aimed at raising awareness of collective heritage, the EU endeavors to determine a common European Identity. One of the most inspiring illustrations of this policy is the project European Capital of Culture, which was an idea generated by the minister of culture of Greece, Melina Mercouri. The project mentioned above provides considerable socio-economic benefits for cities around Europe and accords them recognition throughout the continent and the world. The cities are selected from every part of Europe annually.

City of Novi Sad, Serbia. 2021 European Capital of Culture / Photo Courtesy of AEGEE

Different understandings of European identity

The European Union is composed of the nation-states, which are all diverse and have their own origin, culture, language and traditions. Therefore, it is complex to come to the conclusion that all these diversities are united in one common identity.

Certain number of people view European identity as a political project, which evolved as a product of European Enlightenment. They consider the EU as an institutional machinery for dealing with problems that in the past had shattered peace, undermined stability and prosperity. In spite of the fact that the union has not yet succeeded in constructing a common European sense of “who we are”, the moment falls now. However, the major challenge in this regard is the growing ethnic diversity arising from intensified migration processes since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the enlargement of the European Union, when more immigrants encountered resistance in host countries related to coping with barriers of different cultural practices. Whether these cultural disparities are overcome, the European identity as a project will succeed.

Alternative widely held view perceives the European identity as a contingency. As a consequence of migration for work and education purposes, the process of European integration accelerates and contributes to formation of a common European identity.

Another view states that European identity has a legal dimension. The legal dimension refers to democratic values such as democracy, the rule of law, and human rights. These principles point to Europe’s liberal democratic heritage. They are considered to be universal, not merely European. The first formal EU document that defined the values and fundamental rights for EU citizens was the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. In this document four concepts such as dignity, freedom, equality, and solidarity are represented as “indivisible and universal values”.

Cultural and historical dimensions of European identity pertain to European history and European heritage, which include ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, Christianity (primarily Catholicism and Protestantism), Renaissance, the Reformation, the Enlightenment, and liberalism.

According to Eurobarometer poll 68% of the continent’s population “feels they are a citizen of the EU” / Photo Courtesy of Eubulletin

Another prevailing approach comprehends the European identity as a context. This theory is identical to Constructivism thought, which considers European identity as something that we make of it. However, some authors still argue that the concepts of “European values”, “European identity”, “European heritage” and “European culture” are defined as fixed categories within the framework of EU legal discourse, which cannot be constructed or modified. According to Sanja Ivic, European identity should not lead to new forms of nationalism. It should be flexible and dynamic. The EU documents, which define European citizenship and European identity should not include essentialist assumptions based on the distinction between the “self” and “other”, which exclude and marginalize a number of citizens. It is necessary that the European Union sets out to define a new identity for its supranational agenda as more and more Eastern European countries started knocking on the Union’s doors. An agreement on European identity is crucial for further European Union integration processes and resolving the problems of accession of new member states.

Major findings

- National identity does not prevent us from having another identity. All countries of the continent have different identities, but they have one common European identity.

- Even though European identity is a complex phenomenon, one can clearly state that the European identity means belonging to the community, which respects human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and human rights.

- It is important to reconsider what European Identity means. The term should be more flexible and dynamic as the structure and composition of the EU is constantly undergoing an upgrade.

References

Checkel Jeffrey T. & Katzenstein Peter J. (2009). European Identity (pp. 29-81; 83-111; 193-200). Published by Cambridge University Press.

Ivic, S. (2016). Chapter 5: European Identity. In European Identity and Citizenship – Between Modernity and Postmodernity (pp. 207–252). Palgrave Macmillan.

Sidjanski, D. (2000). The Federal Future of Europe: From the European Community to the European Union (pp. 155-185). Published by the University of Michigan Press.

Urwin, D. (1995). The communities of Europe, A history of European Integration Since 1945 (pp. 7-13). Second Edition. Published by Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Watson, A. (2016). Churchill’s Legacy. Two Speeches to Save the World. Bloomsbury Publishing.

LATEST

Building Europe: Poland’s experience of joining the European Union and lessons for Ukraine

World Health Day 2024: My Health, My Right

EUREKA MEETS EUROPE – opportunities to develop and study. My experience

Can you wear pink in the workplace?

Go where your deepest fears lie: finding the courage to overcome gender barriers in STEM

More campaign pages:

Interested in the latest news and opportunities?

This website is managed by the EU-funded Regional Communication Programme for the Eastern Neighbourhood ('EU NEIGHBOURS east’), which complements and supports the communication of the Delegations of the European Union in the Eastern partner countries, and works under the guidance of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, and the European External Action Service. EU NEIGHBOURS east is implemented by a GOPA PACE-led consortium. It is part of the larger Neighbourhood Communication Programme (2020-2024) for the EU's Eastern and Southern Neighbourhood, which also includes 'EU NEIGHBOURS south’ project that runs the EU Neighbours portal.

The information on this site is subject to a Disclaimer and Protection of personal data. © European Union,