Between reconstruction and restoration: what a Moldovan teacher learned from Italian masters

In Moldova, “conservation”, which in Italy or other European countries means preserving an architectural monument as much as possible, is often confused with “reconstruction” and the erection of a new building resembling the original.

This failure to distinguish between the two can threaten preserved historical monuments. At the same time, there is still no way to qualify as a professional restoration architect in Moldova. This article describes how European programmes are helping to fix this situation, and what kind of knowledge Moldovan architects and builders lack when it comes to preserving historical heritage.

It is almost impossible to become a professional conservation architect in Moldova. There is no such specialisation, either in vocational schools or in the Technical University of Moldova although a few good specialists can be found in the country. Students studying architecture at the University get 60 hours of theory of restoration and 30 hours of lab work during four years of studying. The university does not provide sufficient practical skills in restoration.

“Conservation”, which in Italy or other European countries means preserving an architectural monument as much as possible, is often confused with “reconstruction”

“Conservation”, which in Italy or other European countries means preserving an architectural monument as much as possible, is often confused with “reconstruction” “Conservation”, which in Italy or other European countries means preserving an architectural monument as much as possible, is often confused with “reconstruction”

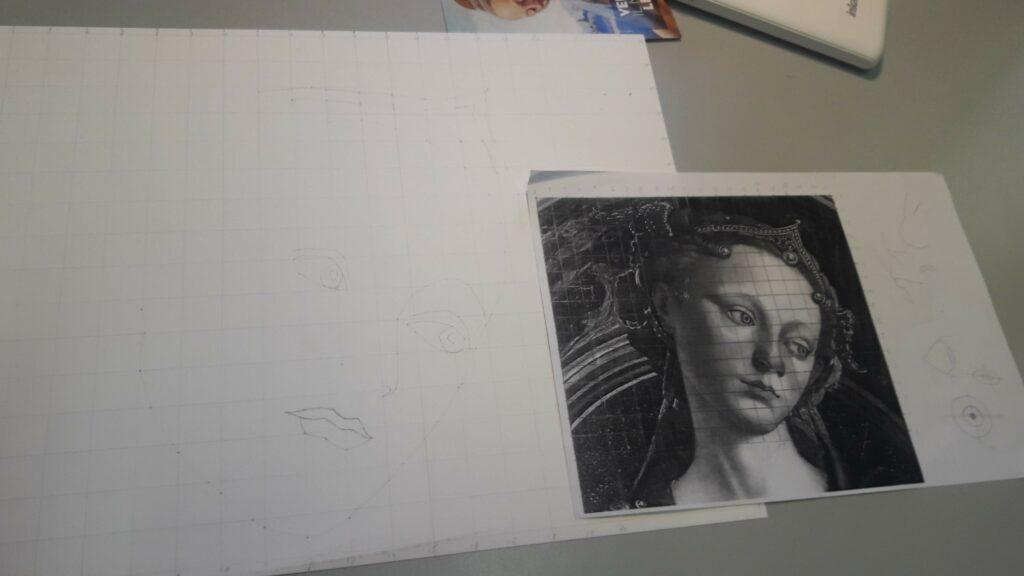

“Conservation”, which in Italy or other European countries means preserving an architectural monument as much as possible, is often confused with “reconstruction” Conservation work performed in Florence (Italy)

Conservation work performed in Florence (Italy) Professional conservation architects in Florence (Italy)

Professional conservation architects in Florence (Italy)

However, in 2018, both teachers at vocational construction schools and profession-oriented universities and architectural and engineering graduates in Moldova had the opportunity to learn from the Italian experience in conservation. With the support of the European Union, a twinning project on “Architectural Conservation”, coordinated by Italian architects and restorers, is being implemented in Moldova: it started in September 2017 and will end in 2019.

One of the participants of the programme, which lasted the entire academic year, was a young teacher of the Centre for Excellence in Construction (professional school), Sergiu Coceas.

Sergiu has been working at the centre for several years, and has been teaching a whole range of specialist subjects, from construction technologies to performance of construction materials. He has a degree in civil engineering, which he received from the Technical University of Moldova.

But aside from his main profession, Sergiu has another hobby – history. This is why he decided to get more involved in the twinning project’s restoration and conservation activities.

Sergiu Coceas, a young teacher of the Centre for Excellence in Construction (professional school)

Sergiu Coceas, a young teacher of the Centre for Excellence in Construction (professional school) Sergiu Coceas with colleagues inspecting a building of a museum in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas with colleagues inspecting a building of a museum in Chisinau (Moldova)

“Many people confuse reconstruction with restoration”

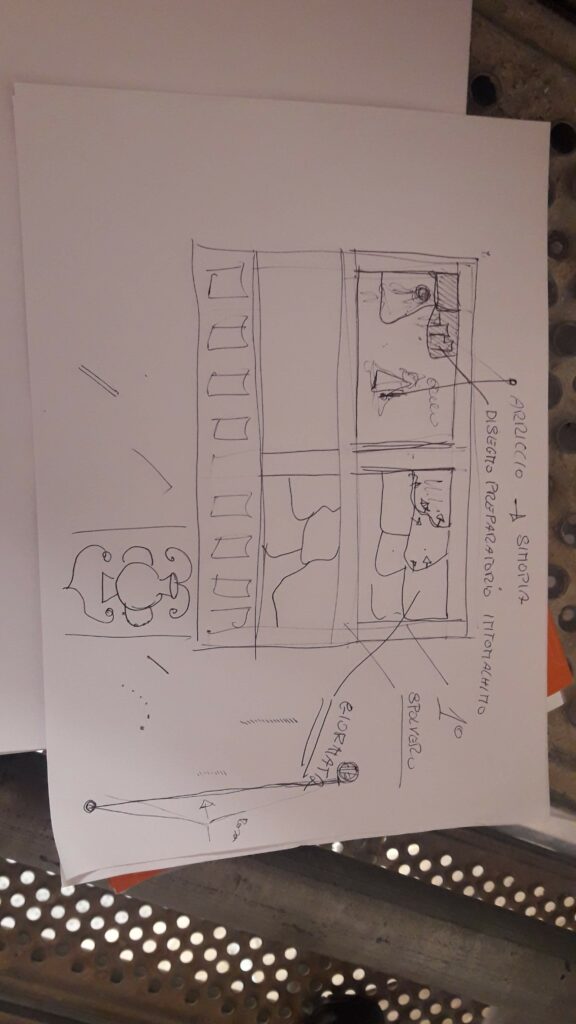

The first part of the training began in Chisinau with Italian professionals in architectural conservation. Under the guidance of Luisa de Marco, the main expert, and her fellow experts, the participants in the training were able to rediscover their capital city, Chisinau, which they previously thought was so familiar to them. After excursions and careful study of architectural monuments, Sergiu admits he began to view Chisinau in a new way.

Part of the training was also to learn how to elaborate a complete conservation project using the example of a real object. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Research suggested the Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street to be used as an educational case study. Built in the 1850s as an orphanage, the building’s use has changed several times. Today, it houses creative workshops, small galleries and rehearsal halls for theatre groups. However, almost no one looks after this monument; the building is in a deplorable state.

Sergiu explains that as part of the training, participants have been learning to develop conservation plans by using one of the large halls of the Zemstvei Museum as an example.

Work began with a detailed study of the building: when, by whom and from what materials it was built; what transformations were made later; why older elements suffered. According to the training’s participants, they were trying to “read the building”. As Sergiu noted, “even the electric wires in the building caused damage to the wall surfaces”.

“We were working on conservation, not reconstruction. Many people in Moldova confuse these concepts. Reconstruction means that we are destroying the old, and building anew from new materials, based on an old design. During conservation, it is necessary to preserve everything as much as possible and to compensate for loss with materials that look like original ones,” explains Sergiu.

However, one thing stood out as the most surprising for Sergiu and his colleagues: “New elements or materials should be added in a way so that they can be distinguished from the old ones while keeping the general harmony of the monument. This is what we were really impressed with during the lectures of the Italian architects: these new elements should be easily removable so that, if after some time better technologies appear or people want to reconsider the previous intervention on the old building, they can simply take them out,” Sergiu says.

The teacher quickly came to the conclusion that in Moldova, restoration is often discussed in vain. During the lectures, there were debates amongst professionals attending the course. What they thought was restoration, the Italians persistently called reconstruction.

“Before this training, for me, restoration and reconstruction were the same thing,” says Sergiu. “We often leave only the facade of the old building, and everything else is rebuilt completely. But this is only a cover-up,” the teacher explains.

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova) Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova) Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova) Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova) Inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova) Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

Sergiu Coceas inside the building of Zemstvei Museum on Shchusev Street in Chisinau (Moldova)

“We act first, and then we think about it”

After the first stage of the training, Sergiu went for a month-long internship in Florence where a lot of conservation schools and workshops are concentrated. Thanks to the programme, he got into the Professional Construction School of Florence, where they teach various types of restoration. Students from all over Italy come to study there.

Sergiu immediately noticed the obvious differences from how they are used to working in Moldova: “At first, I was surprised that everyone was working so slowly,” recalls Sergiu. “No one was in a hurry, it seemed that everyone did whatever they wanted in the laboratory.” But later, he understood from his own experience why the work of a restorer has to move slowly.

During one of his first classes, Sergiu went to work in the field in the Cathedral of Saint Romolus (Fiesole Cathedral), where medieval frescoes were being restored. At one stage of the restoration work, it was necessary to remove the top layer of grey paint and to uncover the earlier white layer. Students were removing the grey layer slowly with scalpels, the very same tools that are used in surgery.

“I was given a small area to work on and I quickly scratched and finished in an hour, although it was a task for the day! Then I finished the second fragment. While I was waiting for a new assignment from the teacher, I looked at what my colleagues’ work looked like and saw that their surface was white as a result but mine was greyish! I was in a hurry and removed the original layer of paint,” recalls Sergiu. This did not cause any particular damage to the fresco, but after that, he radically changed the style of his work. According to Sergiu, sometimes even a day was not long enough to clear the little fragment he was given.

“In Moldova, we often act first and only then take the time to think. But I discovered that in restauration, we first need to reflect before taking action. Only this way can we find out the most suitable methods not only from an economic point of view, but we can also calculate how long it will take, what materials are needed, etc.” the teacher explains.

In the vocational school’s laboratory, Sergiu not only became acquainted with conservation methods, but also saw how a fresco emerged from behind a dull painted surface. Students reproduce the old techniques themselves, in order to understand how to restore the images later.

After returning from Florence, the lack of specialists in Chisinau became even more obvious to Sergiu: “I have not yet seen examples of restoration per se. Everywhere we went with Italian professors and later, everywhere I went by myself in Chisinau, there was only reconstruction,” says Sergiu.

Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence

Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence At the Professional Construction School of Florence

At the Professional Construction School of Florence At the Professional Construction School of Florence

At the Professional Construction School of Florence Inside a church in Florence

Inside a church in Florence Conservation work performed inside a church in Florence

Conservation work performed inside a church in Florence

“We will finally have Moldovan restorers”

Sergiu brought from Italy not only the knowledge he gained during his studies in the laboratory, but also an enthusiasm for making it possible to preserve architectural heritage in his country.

“We were told in Italy how one person inherited 3 million euros. He bought a palace for 2 million euros and planned to make renovations there and open a hotel. He bought it but could not start the renovation work. He was asked: ‘Did you read the contract? It is yours, but you cannot change anything there,’” recalls Sergiu. Although he still opened the hotel, the man had to invest 1 million euros into the restoration and this money was enough for only one part of the building. There are very significant fines in Italy for violating the law in this area. And people prefer not to take such risks.”

Sergiu believes that, as it stands, specialists in Moldova are not mentally prepared for such changes: they do not have the necessary skills. In his opinion, the “political factor” also slows down the process of tightening the rules and laws in the area of heritage conservation.

“I hope that with the development of tourism, a change in mentality will occur, and we will learn to preserve what we have. After all, this is our history,” says Sergiu. He now considers restoration a “special art”.

After the trip, Sergiu intends to fill the gap of educational programmes for future restorers. He says that during the course, which is taught to future architects at the Technical University, “they talk more about reconstruction and not restoration”. Now, he really does hope to fix this.

Sergiu has already started to propose changes to the curriculum for construction students so that they can also be taught conservation during their studies at the Centre of Excellence where he teaches.

Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence

Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence .

. Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence

Sergiu Coceas at the Professional Construction School of Florence .

. Sergiu Coceas during his trip to Florence

Sergiu Coceas during his trip to Florence

“I also have a dream to organise a full-scale continuing training course specifically for restoration, so that trained people with some kind of knowledge can update their skills in the field for the sake of the national heritage,” says Sergiu.

During his studies in Florence, he was inspired by various workshops, including one on the restoration of antique furniture. He says he will try to open extracurricular activity groups in the centre for those who want to learn how to restore not only buildings but also old furniture.

The teacher is convinced that such programmes would help solve the problem of the lack of skilled human resources: “Then, we will finally have Moldovan restorers, because many companies complain that specialists for individual projects have to be ‘imported’,” says Sergiu.

Author: Olga Gnatcova

MOST READ

SEE ALSO

No, time is not on Russia‘s side

How to open an art business in Moldova: the experience of Alexandra Mihalaș

Be one step ahead of a hacker: check simple cybersecurity tips!

How to act and move on: strategies for women facing discrimination and online harassment

‘Learning is not a process but a journey’: the example of a school in Orhei

More campaign pages:

Interested in the latest news and opportunities?

This website is managed by the EU-funded Regional Communication Programme for the Eastern Neighbourhood ('EU NEIGHBOURS east’), which complements and supports the communication of the Delegations of the European Union in the Eastern partner countries, and works under the guidance of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, and the European External Action Service. EU NEIGHBOURS east is implemented by a GOPA PACE-led consortium. It is part of the larger Neighbourhood Communication Programme (2020-2024) for the EU's Eastern and Southern Neighbourhood, which also includes 'EU NEIGHBOURS south’ project that runs the EU Neighbours portal.

The information on this site is subject to a Disclaimer and Protection of personal data. © European Union,